I had this discussion with a trainee today, and it's worth sharing here.

We were adding saturation to a landscape photo, and the conversation turned to grass. Specifically, the fact that

grass ain't green! Well, not always.

Almost as soon as we were old enough to hold a crayon, we were taught to draw green grass and blue skies (and houses where the windows are much higher than the doors, for some reason, but that's another matter!). But this isn't necessarily the case. Technically speaking, grass usually has a much stronger yellow component than green, and skies are invariably stronger in cyan than blue, unless a filter has been used in the capture.

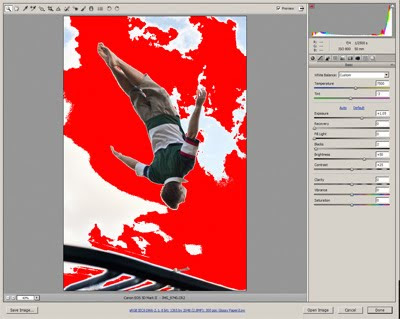

To the average person, this doesn't matter a damn. And even to a photographer, it's not always a problem ... until you need to edit those elements. If you've ever used Hue/Saturation or Selective Color to adjust grass or a sky, you'll know what I'm talking about. If you choose "Greens" or "Blues" respectively, your adjustments tend to be weak at best. But if you look at the colours the way Photoshop looks at them, you'll realise that "Yellows" and "Cyans" are where the answer lies.

I guess there are dozens of examples of this. Green apples are another one that springs to mind - not green at all! So if you're having trouble editing a particular colour, stop for a moment and try to think like Photoshop - is it really the colour you think it is?